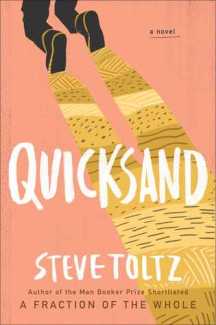

This is the long-awaited second book of Steve Toltz who was shortlisted for the Booker in 2008 for A Fraction of The Whole (which I haven’t read). I have to say at the outset that I wearied of it well before the end. Its incessant wisecracking verve left me in its wake. But that’s me, the product of a twentieth-century book culture. Toltz, like many readers who will love the book, is of a different generation, and one of the most interesting things for me in reading it was the way it exemplifies the divide between the children of the ‘book culture’ and the children of these fast-moving multimedia times, a new idea coming along every minute. I’m in no doubt of Toltz’s talent; commentators have mentioned, rightly, Bellow, Roth, Woody Allen, David Foster Wallace and Dave Eggers. I’d throw in the early Peter Carey, the Carey of The Tax Inspector and Illywhacker.

Australian by birth, Toltz has lived a lot of the last decade overseas – in Canada, Spain, Paris, and currently New York – and even if his setting and characters are Australian, the American influences are loud and strong. The manic life of Aldo Benjamin and the constant repositioning of angles reminded me that Toltz has previously worked as a screenwriter. It’s a book that has its eye constantly on the audience, saying, ‘Look at my tricks!’ This is not intended to denigrate the book or to suggest that Toltz isn’t genuine. It’s just the kind of product it is. There is a downside, of course, to this parade of cleverness, and that’s the sacrifice of a certain weight and depth of feeling that is humming in the background but rarely given breathing space in the frenetic pace of the book and the deliberately anarchic grab-bag of thoughts that seems to be irresistible to Toltz.

Here are two extracts as an example, first Liam Wilder’s voice:

The fact is, I didn’t really understand why Aldo’s love for Stella was so robust. It was a nuisance for everybody. When I reached the station doors, I turned back to see her, unmoved under the streetlight, still watching me. I saw what he saw: the artist/songwriter, the frantic mother, the highly intelligent, no-nonsense, no-bullshit and weirdly increasingly youthful incarnation of some dangerous, angry beauty. For a brief moment I got to feel what he felt, and the contrast to my own tepid emotional tumult with Tess made me realise that in the world of love I was a straggler, a craven magpie, a lousy poet who, as Aldo said, was a stickler for reality and all the poorer for it. (203)

and then Aldo’s, after he’s taken an overdose in yet another suicide attempt:

The dying epiphanies, only five in number, came thick and fast:

1. There must be bacteria in plastic banknotes. I’m sure I got E.coli from a fiver.

2. Idea for a neurotic ladies’ man: a product line of condoms made of antibiotic-laced polymer.

3. Whenever someone said to me, What would Jesus do? I should have said, They say that the best indicator of future behaviour is past behaviour, and then walked away.

4. All those times people pretended to be impressed, nobody really believed that I could tickle myself – they all thought I was faking.

5. Birth is irreversible because death is not its true opposite. (300).

In spite of its multitudinous jokes, puns and one-liners, the material of the book is grim. Aldo Benjamin is paraplegic, in a wheelchair, and recently released from prison when we meet him. His friend Liam is a failed writer, an accidental policeman, and separated from his wife and child. Male crisis is the book’s material. Liam, a writer who has failed at all his previous projects, now realises that he has his ‘natural subject’ in Aldo:

The last cigarette shaken out of the soft pack of ideas: my sad old friend, who I’d met in 1990 – a two-decade gestation period. Other people were mere vapour to me, but I knew his inadequacies by heart. No facile invention necessary; I’d give readers the realest person I knew. Of course, his life was anything other than ‘the way we live now’. Nobody lives like him and lives to tell the tale. I’d tell his tale! I’d curate an exhibition of his foibles and follies. I felt luminous, intrepid, like a correspondent embedded in hell. I was going to make my report. Finally! My natural subject. (70-1)

Part of the book is Liam’s manuscript, provisionally titled Aldo Benjamin, King of Unforced Errors, the story of Aldo’s catastrophic career of big ideas coming to grief. Another chunk, occupying 160 pages of the total 435, is an address by Aldo to the court at his trial for murder, and this was the section that gave me most trouble, because undiluted Aldo is pretty hard to take. His is a whirlpool ego that sucks everyone into it and dashes most of them against the rocks, and once you learn that – very early on – there’s not much more to be said or shown. It may be that this section shows us a deeper and more complex version of Aldo. I can’t say; I was deafened, dizzied, swamped by verbiage.

Perhaps, I thought, this is today’s version of the picaresque novel. Instead of a Tristram Shandy or a Don Quixote travelling far and wide, we have the travels within the ego of an extreme personality in a world that that he stubbornly resists, even though it holds all the cards.

Aldo Benjamin is a character who was edited out of A Fraction of the Whole and who now has a book all to himself. Surely Toltz has worked this vein out. It will be interesting to see where he goes from here.

Not sure I’d want to venture there and read that book either.

Leslie

As a rule we try not to write about books we really didn’t like. But in this case as I said it’s a question not of the writer’s ability but of the changing zeitgeist, and we thought it was interesting from that point of view. As I said, many people will love the book – and it has had some great reviews from people with more critic credentials than we have!

Yes perhaps you’re right about “changing Zeitgeist.” Doesn’t sound like something I’d enjoy but it’s probably a generational thing.

No, I don’t think it’s for you.

I don’t think this is for me either, as the style and subject matter would probably weigh me down. It’s very useful to read your review, though.

We’re interested enough to read the first book, ‘A Fraction of The Whole’ so we may post on that a little later.

Whirlpool ego? Not appealing

June

No, I think you would tire of it as I did.