How’s this for a start in life?

Under whirring helicopter blades, a young woman holds her newborn baby as she is pushed in a wheelchair along the runway of the island airport to meet a man in a strait-jacket being pushed in a wheelchair from the other direction.

That was the first day of Amy Liptrot’s life. Her mother had just given birth in a small hospital, her father, having had another severe episode of mania, has been sectioned under the Mental Health Act and is being taken to a secure unit in Aberdeen. Orkney is the island where they live. Liptrot continues,

My Mum introduces the man – my Dad – to his tiny daughter and briefly places me in his lap before he is taken into the aircraft and flown away. What she says to him is covered by the sound of the engine or carried off by the wind.

But Amy Liptrot’s story is not one of a childhood lived under the shadow of mental illness or abuse. ‘Mum’ sticks around until the children are grown up and then becomes a born- again Christian and leaves the farm. ‘Dad’ has his ups and downs, sometimes going on wild spending sprees, at others lying motionless in bed for days, but Amy and her brother Tom seem to live remarkably free and unfettered lives. They deliver lambs, dispose of dead sheep, climb over rocky cliffs, go to school and party.

By the time she is eighteen she really likes to party and she can’t wait to get off Orkney. She heads to Edinburgh for University but she wants to be in London, at the centre of things. She has tried booze and some of the milder forms of dope at school on Orkney but she wants the big time. To be in London, to be cool, to be edgy. She often uses the word ‘edge’. That’s how she wants to see herself, a risk-taker who lives on the edge. But perhaps she forgets that on Orkney and the remote islands that surround it, unwanted objects like dead sheep and broken cars get thrown over the edge into the sea far below. The edge is also the limit and if one falls everything is lost.

At first she is working for magazines, and hanging out with the cool crowd, partying all night, drinking, taking handfuls of pills. Her drinking increases but she has not quite lost control when she meets her American boyfriend. But she knew she would one day:

…there were gaps when I wasn’t there. I’d drink until my eyes went dead.

And soon it gets so she sneaks out at night on her bike while he is sleeping, looking for the all-night suppliers of booze. She is drunk every day, always crying, a disaster. One night when she is out riding on the towpath at dawn her bike crashes into the canal.

Pushing my bike out with one shoe on, I came home to him bleeding and crying. It wouldn’t be long until he couldn’t take it any more.

By the time she has spent ten years in London her life is right out of control. She has lost friends, has no job, no money, nowhere to live. And she has started having seizures, which indicate the beginning of alcohol-related brain damage. Eventually she submits herself to a government-funded four month live-out rehab program. She wants to be free of her destructive addiction, but finds it hard to accept the faith-based nature of AA. She survives the course, one of only two successful graduates from her group. Now she has nowhere to go but back to Orkney.

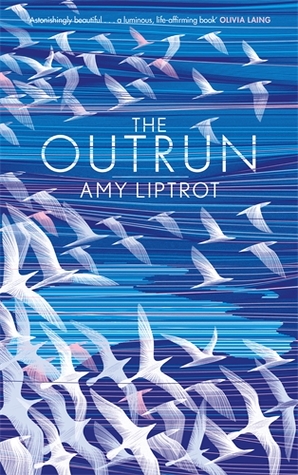

This book, which has just won the 2016 Wainright prize for nature writing is largely about her time in Orkney on her father’s farm, the largest field of which, The Outrun, gives its name to this book. It is also about Liptrot’s struggle to lose the desire, always gnawing at her, to have a drink, just one drink, and to find other things in life with which to replace it. The account of her growing interest in winds, tides, clouds, birds and galaxies is fascinating. She spends a winter on a small island off Orkney called Papay and sees extraordinary sights. In her first few weeks there she sees the aurora called the Merry Dancers:

Tonight the whole sky is alive with shapes: white ‘searchlights’ beaming from behind the horizon, dancing waves directly above and slowly, thrillingly, blood red blooms. It’s brighter than a full moon and the birds, curlews and geese, are noisier than they usually are at this time of night, awakened by a false dawn.

By the end of her story Liptrot has been sober for two years. She has found swimming in the ice cold sea gives her a thrill like nothing else, and is gradually working on some of the remaining goals of AA in her own way. But it is the natural world that has saved her.

Liptrot now lives between Berlin and London. I look forward to reading more from her soon. You can find out more about her work on her tumblr site amyliptrot.tumblr.com

So this is an autobiography?

Leslie

Yes this is very much about her, but I would put the book in the category of creative non-fiction where the author’s life is very much part of the account of a non-fictional subject. As here, weather, declining species, the constellations and the history of settlement in the Orkney Islands are among the topics explored alongside the struggles of her own life.

If I remember correctly a lot of her struggles had to do with a fast paced life style and addiction.

Leslie

But my goodness you have to give her points for beating the addiction. What a struggle!

Agreed, that does take “intestinal fortitude”.

Leslie

Creative non-fiction sounds like a good way of describing this book. Certain elements of your commentary call to mind Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk, especially the focus on the healing power of the natural world.

Yes I do quite like that genre, although sometimes it can be too over the top as with Hunter S Thompson et al. I think Helen Macdonald’s book is about dealing with grief?

Yes, that’s right. She turned to the training of a goshawk as a way of dealing with the emotional turmoil following the sudden death of her father. I found it very moving, but not in a mawkish or overly sentimental way. Quite a fine balance to tread with some of these books…

I will read her book. I didn’t think Amy Liptrot’s book was perfect by any means. Most of the stuff about Orkney was first published on the website Caught by he River and it shows.

Oh, that interesting as it’s the stuff about the island that really appeals to me. I keep meaning to make time to read some of the new nature writing that has emerged in recent years, Kathleen Jamie in particular. But then again, there are so many other books I want to read too. It’s proving impossible to fit everything in right now. *sigh*

The eternal problem, how to read more. As a child I did little else. Sometimes I would read ten books in a day.

That’s impressive!! You have an excellent foundation for your current life.

Although I must say my reading wasn’t exactly high literature. A great deal of Enid Blyton with some P G Wodehouse in the mix.

We read voraciously, although my mother believed that there could be too much, so she tried to limit it. When we were in about 4th grade, my dad started sending my older sister and me to the library to check out Perry Mason and Rex Butler, etc. murder mysteries for him, so we read all of them, plus Nancy Drew, any kind of science thing that we got our hands on, the “classics” — often somewhat abridged, the Readers’ Digest collections from my aunt’s house, lots of books about Catholic saints, etc. I didn’t really find Wodehouse until after college, and then made a pretty complete collection of him. Ditto Dorothy Sayers, GK Chesterton, and many of the other English authors that the small town library didn’t have.

We read those English classics from our father’s library, to say nothing of Billy Bunter, The Boy’s Own Annual and bound editions of Punch from his early youth in the 1920’s

A treasure trove . . . I never understood Punch. To this day, I don’t “get” it, although I haven’t tried in the past decade, so maybe I should give it another go. Perhaps it’s something with which one must be inoculated from an early age.

I think we mostly liked the pictures.

And the cartoons? Or you liked the cartoons because they were pictures? We did fight over who got to read the encyclopedia volumes that had the most pictures in them.

This was the artist I liked who drew characters with big heads. I didn’t understand what it was about but thought it was funny.

He risk taking and quest for excitement suggest the booze may have been self medicating her own moods?

She considers that possibility and dismisses it quite thoroughly, but given her subsequent high consumption of Coco Cola and cigarettes and thrill seeking behaviour one does wonder.

Speaks to the resilience of Amy Liptrot, the power of nature to heal us, and may that cold water swimming continue to thrill.

A very interesting review and I enjoyed the commentary following just as much.

Thank you to everyone. 🐞

Thank you, JoHanna.What a model citizen of the blog world you are!

What a gracious thing to say. Thank you. 🐞