You have destroyed/this lovely world

There’s a huge amount of stuff in All For Nothing – dinner sets, underwear, dolls’ houses, silver teaspoons, bedsheets, table linen, dresses, suits, fur hats and hats with feathers, telescopes, books, letters, photographs, maps, brochures, lutes, sewing machines, grandfather clocks. Possessions stand for people’s disbelief in what’s happening. Crates in the old drawing room of the Georgenhof estate in East Prussia hold the possessions of the von Globigs’ relatives in Berlin, stored for safekeeping till the war is over.

Then they danced over to the summer drawing room and its wide but ice-cold expanses, all white and gold. The windows looking out on the park were frozen, and against the wall stood a row of crates roughly cobbled together and containing all the worldly goods of the cousins in Berlin, who didn’t want to lose their table linen and clothes at the last minute. In fact, there was more room here for turning right and left. (41)

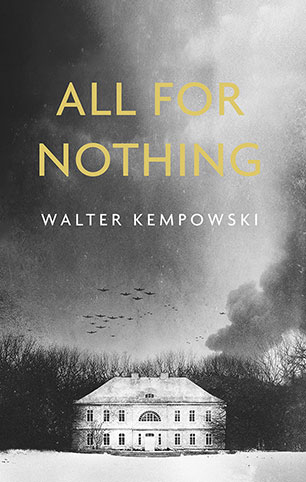

This wonderful image gets right to the heart of the story: people dancing around a pile of possessions in a freezing, decrepit old house that was once grand. These days there are lots of travellers on the road, on carts, pushing prams, wheeling bicycles or pulling sledges, and the Russian army is advancing as the Third Reich crumbles, but Katharina von Globig, her 12-year-old son Peter and their family retainer Auntie live in the old family house as if frozen in time.

The Russians? Would they be coming here? asked Auntie, putting the cups back in the cabinet neatly. At that moment, it may have occurred to her that such a thing was possible (25)

Katharina idles away her days smoking, reading, giving herself an occasional treat of real coffee, and dreaming of the past, while Auntie busies herself with the practicalities of making scarce food go round and chivvying the farm workers. Katharina’s husband Eberhard is in Italy with the German army in charge of rounding up all the food he can to send back to Germany.

The book’s chapters are like movements in a musical composition with themes introduced and recapitulated in different keys. Travellers pass through the house in the first half of the book: the political economist, the violinist and the soldier, the painter; across the road is the housing development known as The Settlement, full of “what you might call ordinary people” whose trustee is the Hitler lookalike Drygalski, for whom the rise of Hitler has meant an escape from poverty; there are “foreign laborers” – Czech, Italian, Romanian, Dutch, French, presumably prisoners of war – in the settlement, and the two maids are Ukrainian, lured away from home by Eberhard’s promises of life in Germany. There’s Dr Wagner, the schoolmaster who comes to the house to tutor Peter. He’s been teaching history, German language and literature and Latin in the village school for many years But now that old building was as cold as ice, however much you tried to heat it (62) and he regularly marks on the old school photos the faces of his students killed in the war. So, stuck in this little outpost in the snowy emptiness of East Prussia, we are constantly reminded of the long sweep of German history, German culture and learning, German song and poetry (the text is sprinkled with quotes from songs and poems), all of this being blown apart around these people who can’t or won’t see what’s happening. I’ll say no more about the reason why they finally leave than the book’s cover says: “a decision to harbour a stranger for the night begins their undoing.” The dreamlike movement of the first part of the book snaps into practicalities and it’s tough, shrewd Auntie who takes control. This happens quite late in the book (not till page 242 of 342 pages), the long slow movements of the first chapters suddenly being replaced by dissonance and staccato. Fragile, dreamy Peter, the purposeless child of the early part of the book, is remade as a shrewd survivor.

One of Kempowski’s major works was the 10-volume Echo Soundings, a collage he built up over ten years from thousands of personal documents, letters, newspaper reports, and autobiographical writings of people caught up in the war. All For Nothing bears the marks of this work in the many individual stories woven into the story of the von Globigs. In fact the early part of the book, with the series of travellers taking brief shelter in the house, reminded me of Everyman.

One dark evening the front doorbell rang. The man who had rung it was getting on in years, wore an unusual cap, and walked on two crutches (10)

The next guest could be seen coming from far away, silhouetted against the horizon and crossing the field, enveloped in swirling snow. Crows with ragged wings dived down on the fluttering figure. (29)

There are many many books dealing with the catastrophe of Hitler and the blowing-apart of Europe as it was, many books that deal with the human weaknesses and strengths that war shows up, many books that deal with the refugee experience. All For Nothing is about all these things, but it is unusual in the leisurely, mournful way it unfolds the big tragedy through immersion in so many individual tragedies. Dr Wagner, for instance:

Now, when he sits alone in his room, he often thinks of the good times, of home, of eating fried flounders with his mother beside the River Pregel. And he is sorry that he wasn’t nicer to her.

“Time, time, you can never turn it back, my boy.” And he would stand up and look at the cuckoo clock, with its pendulum swinging quickly back and forth, left to right and vice versa, and the little door is already opening, and the cuckoo calls out of the clock whether you want to hear it or not. (71)

Kempowski takes his time and allows all these human beings to show themselves to us, without judgment, and with a sure-handed grace and power. It was his last book, and a fitting memorial.

Thanks so much for your book introductions and for your always excellent writing! All the best, my friends! 🙂

And to you Fabio. I’m just about to head over to your blog and see what naughtiness you’re up to.

Your commentary on the house made me think of Sybille Bedford’s semi-autobiographical novel ‘A Legacy’ which I’m reading at the moment. The time period is earlier (pre-WW1), but there is the sense of a world slipping away…

I think you’ve written about Sybille Bedford before, but I’ve never read her as far as I can recall. I think you’d like this book.

The breadth of human experience nicely shared in a vicarious fashion. That is the greatness of literature, you get to experience the troubles and joys of others, in other times all the while cocooned in quite room reading a book. Many a lesson learned that way.

Leslie

Just can’t understand people who don’t like reading.

Me too.

Leslie

Now I have read the novel, I see what an outstanding review of a tremendous book this is.

For some reason, Josie, I was thinking about this book yesterday. I think it’s one of my all-time great books. That scene in the ballroom is unforgettable.